Search for a Second Earth – the Earth 2.0 (ET) Space Mission

-

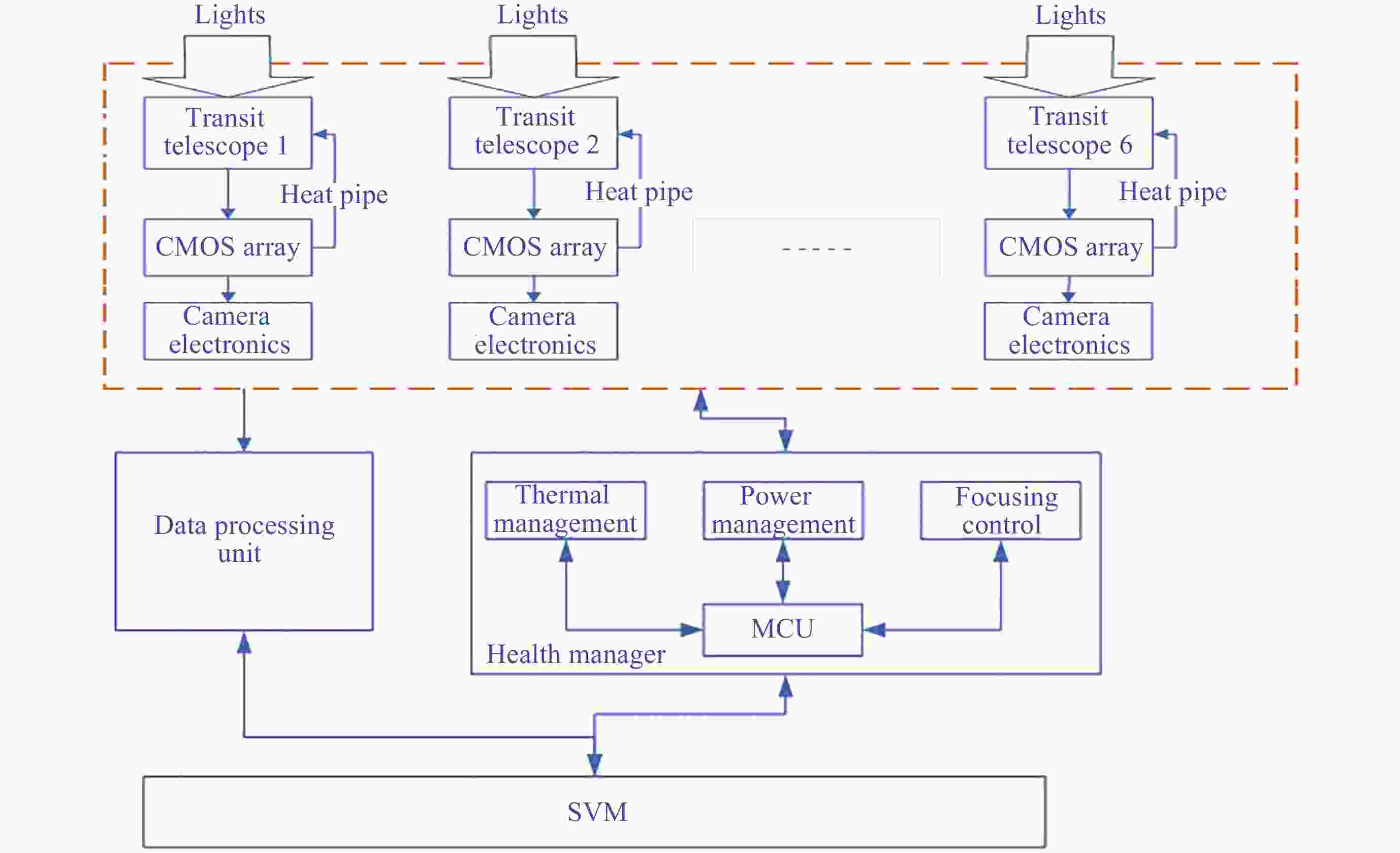

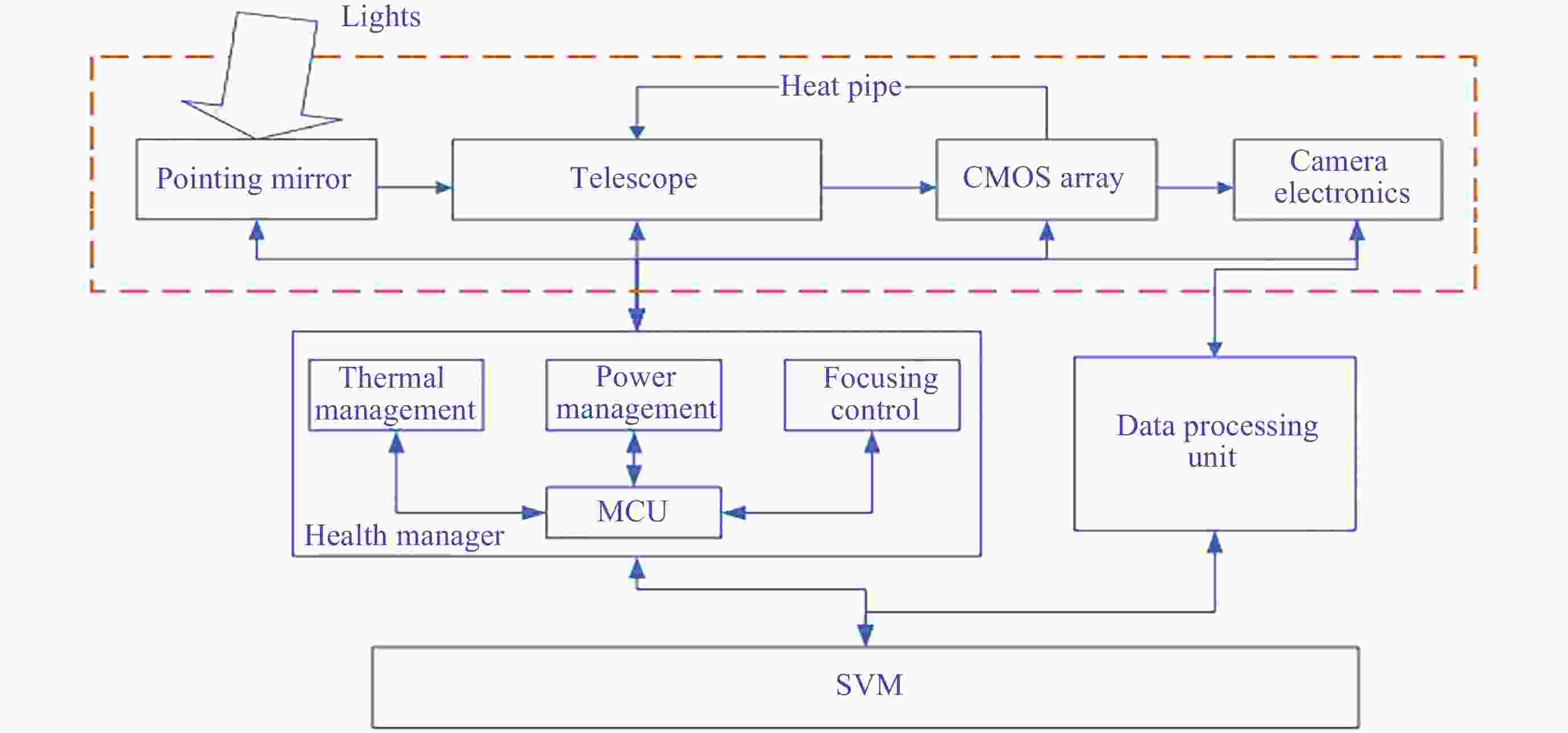

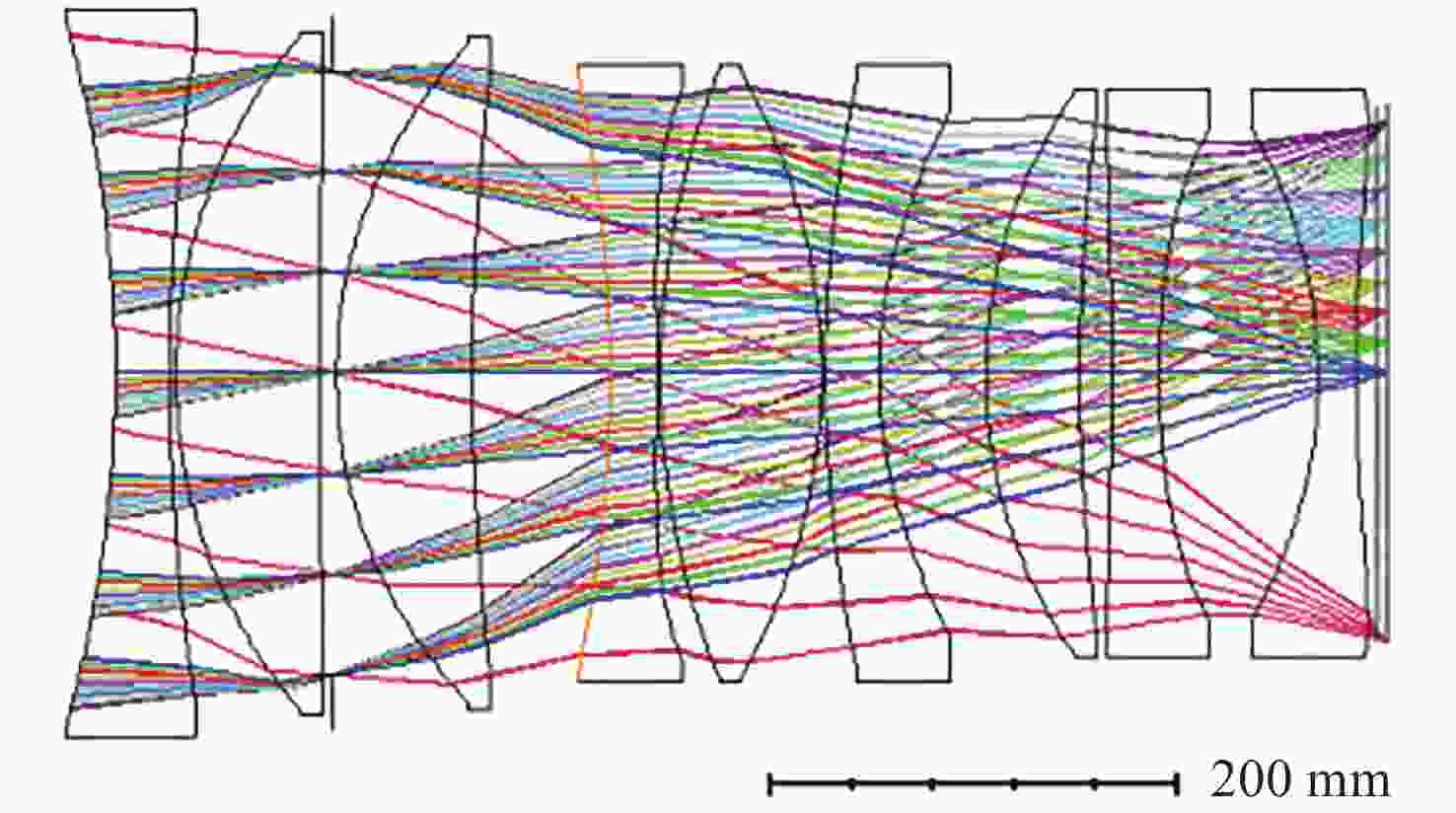

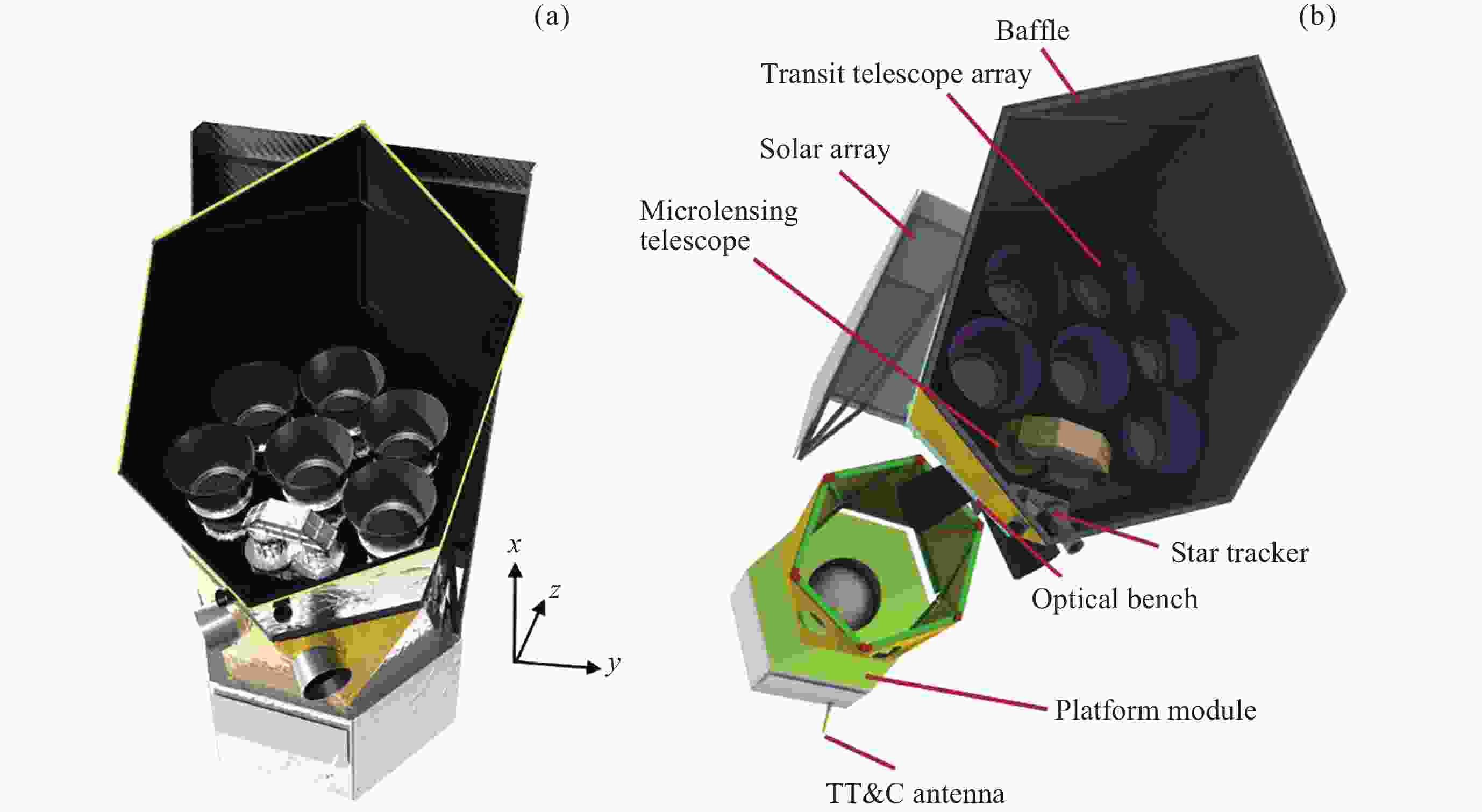

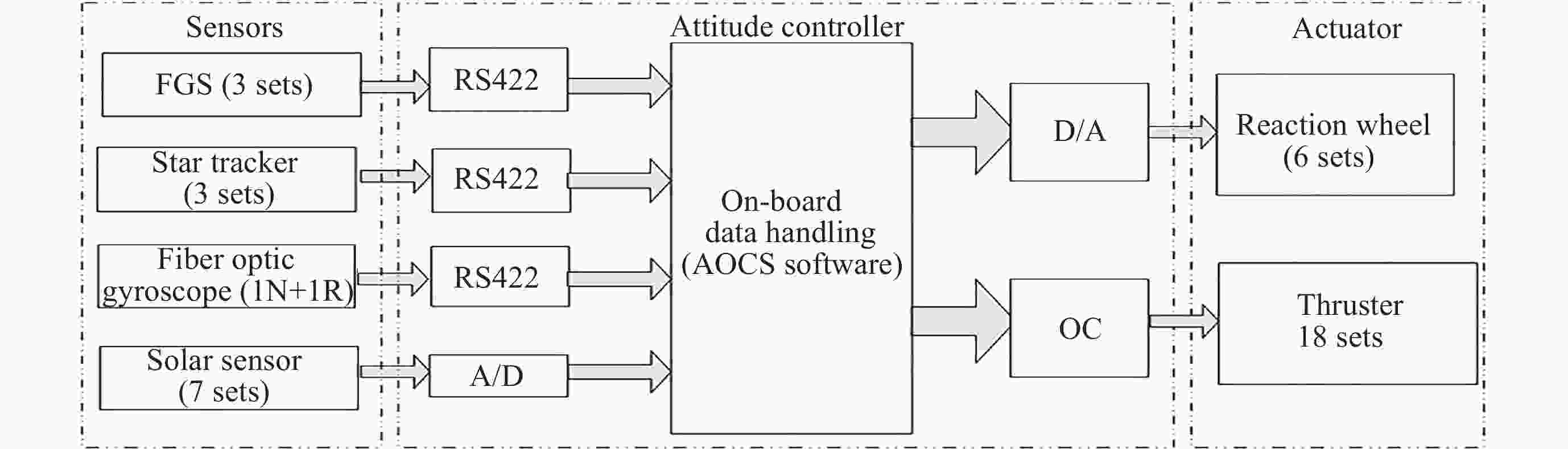

摘要: 系外地球科学卫星(ET)将通过采用空间大视场超高精度测光这一关键技术在国际上率先突破生命起源中的系外地球存在及其演化这一重大前沿科学问题. ET卫星将在日地拉格朗日L2点晕(Halo)轨道部署由6台广角凌星望远镜和1台微引力透镜望远镜构成的空间天文台, 结合凌星法和微引力透镜法, 利用空间超大视场和超高精度的光学测光观测, 首次发现富有重要意义、被广泛关注的系外地球, 并确定其发生率, 对目前了解甚少的类地行星和流浪行星进行国际上第一次大规模的种群普查, 首次发现流浪地球, 并确定其发生率, 揭示类地行星和流浪行星起源, 为地外生命探寻提供候选者和新方向. ET卫星的观测结果、统计研究以及和对理论的检验将回答系外地球在宇宙中有多普遍, 类地行星是如何形成和演化的, 流浪行星又是如何起源的这些亟待解决的前沿科学问题. 对ET卫星发现的系外地球样本的后随观测, 将精确测量其质量、密度和大气成分, 有助于深入分析宜居性特征. 此外, 对ET新发现的大量各种系外行星样本的研究, 以及对理论的检验将推动这些种类的行星形成和演化规律的更深入认识, ET的大量高精度、高频次和长基线测光数据将推动星震学、银河系考古学、时域天文学、双星和双星黑洞等领域的研究.Abstract: The Earth 2.0 (ET) mission will pioneer the international breakthrough in the frontier scientific issue of the existence and evolution of Earth 2.0s (or exo-Earths) in the origin of life by adopting the key technology of ultra-high precision photometry with a large field of view in space. The ET mission will deploy a space observatory consisting of six wide-field transit telescopes and one micro-lensing telescope in a halo orbit at the Sun-Earth Lagrange L2 point. Combining transit and micro-lensing methods, utilizing the ultra-large field of view and ultra-high precision optical photometry observations in space, the ET mission will for the first time discover historically significant Earth 2.0s and determine their occurrence rate. It will conduct the first large-scale survey of terrestrial-like and free-floating planets, discover free-floating Earth-mass planets and measure their occurrence rates, reveal the origins of Earth-like and free-floating planets, and provide candidates and new directions for the search for extraterrestrial life. The observational results, statistical studies, and theoretical tests of the ET mission will answer pressing frontier scientific questions such as “How common are Earth-like planets in the universe”, “How do Earth-like planets form and evolve” and “How do free-floating planets originate”. Follow-up observations of the Earth 2.0 samples discovered by the ET mission will precisely measure their mass, density, and atmospheric composition, contributing to an in-depth study of their habitability characteristics. Moreover, the study of the large number of various exoplanet samples newly discovered by ET, as well as tests of theories, will promote a deeper understanding of the formation and evolution of these types of planets. ET’s abundant high-precision, high-cadence, and long-baseline photometric data will advance research in fields such as asteroseismology, Galactic archaeology, time-domain astronomy, binary stars, and binary black holes.

-

Key words:

- Exoplanets /

- Terrestrial-like planets /

- Habitable zone /

- Transit /

- Microlensing /

- Photometry

-

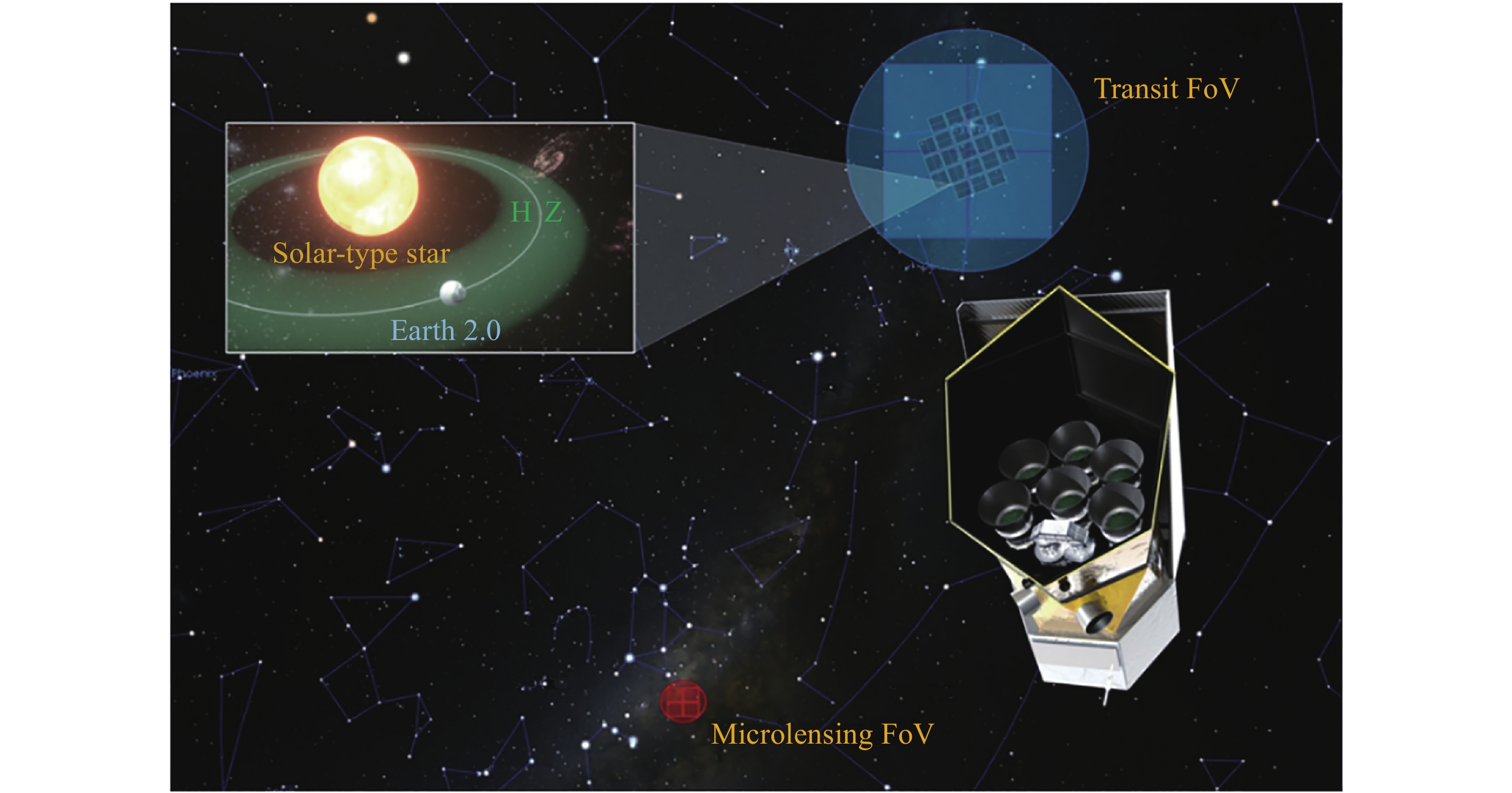

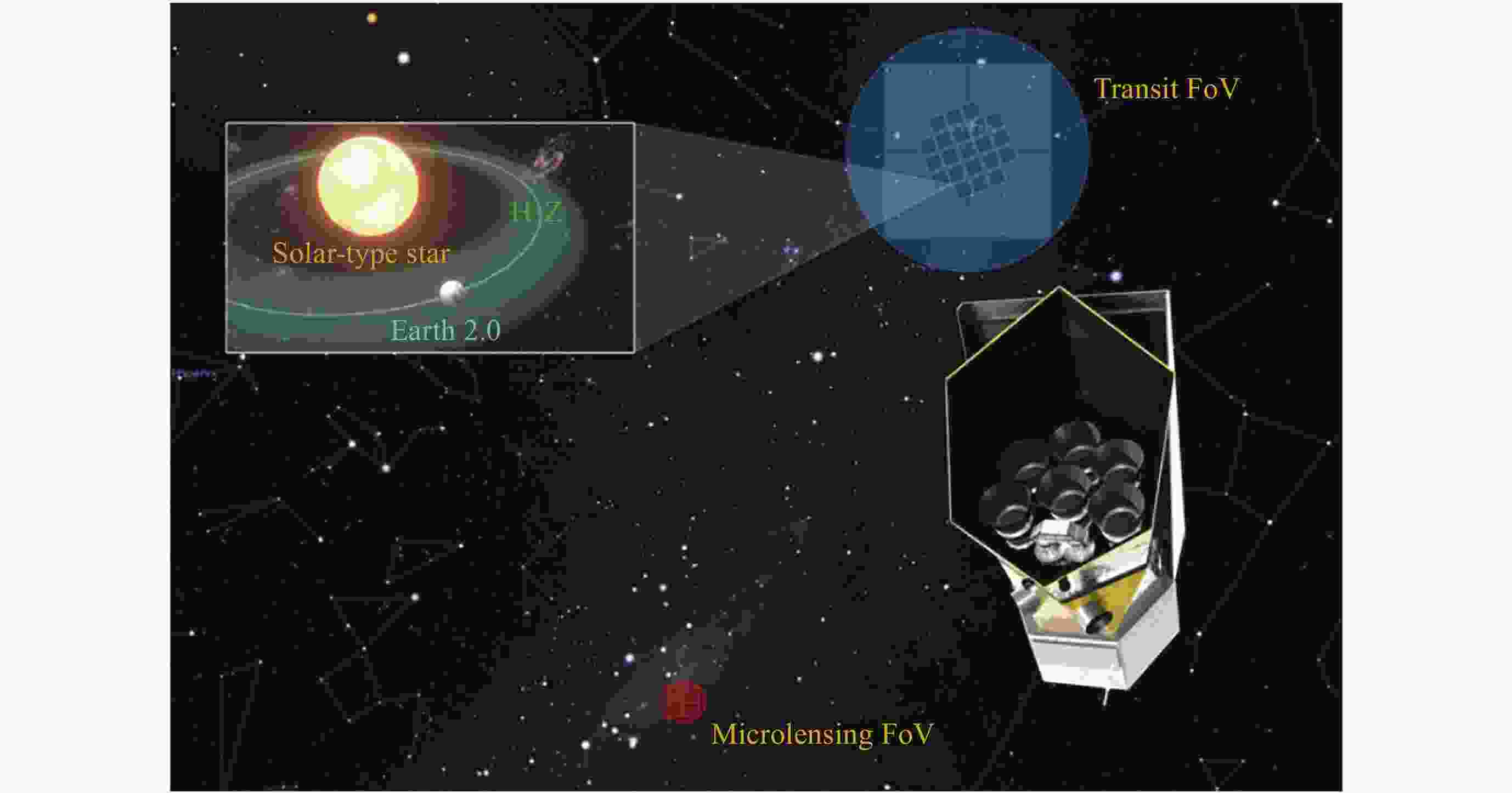

图 1 ET空间天文台. ET将凝视图中蓝色圈内区域4年时间, 旨在发现围绕类太阳恒星周围的宜居地球大小(0.8~1.25 Re)的行星(系外地球或地球2.0). 由于ET覆盖Kepler已观测的天区(图中网格区域), 结合Kepler已有的4年观测数据, ET的产出将极大地拓展长周期行星(包括地球2.0)与多行星系统的发现. 此外, ET还将观测银河系核球区域(红色天区), 利用微引力透镜法搜寻长周期冷行星和流浪行星, 包括流浪地球(由 Innovation期刊提供)

Figure 1. ET space observatory. ET will observe the area within the blue circle for four years to discover habitable Earth-sized planets (0.8~1.25 Re ) orbiting sun-like stars (Exo-Earths or Earth 2.0). Since ET will cover the region previously observed by Kepler (the gridded area in the figure), combining it with Kepler’s existing four-year observational data will greatly expand the discovery of long-period planets (including Earth 2.0s) and multi-planet systems. In addition, ET will also observe the Galactic bulge region (the red area in the image), using microlensing to search for long-period cold planets and free-floating planets, including free-floating Earth-mass planets (provided by the journal Innovation)

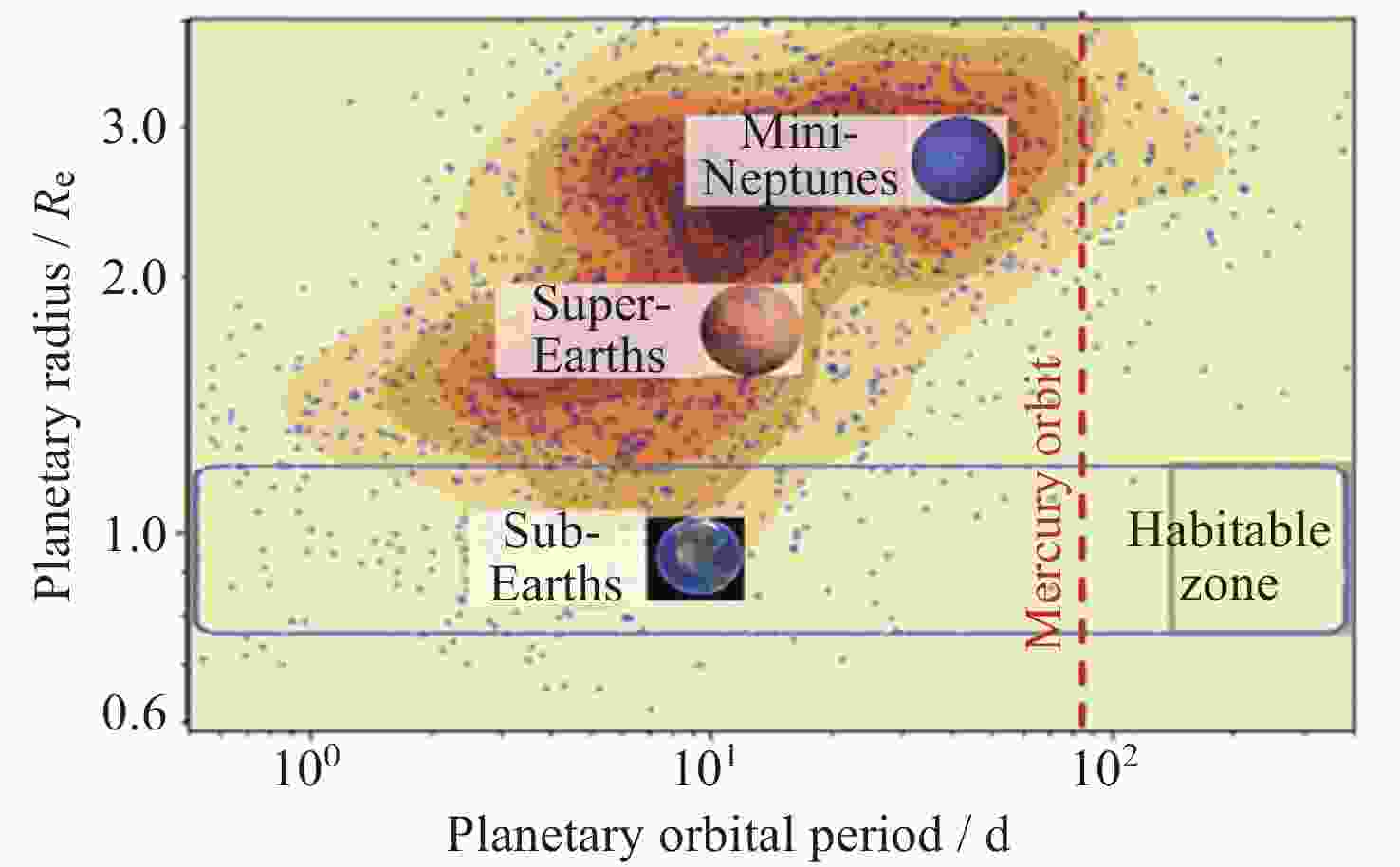

图 2 Kepler发现的行星半径和轨道周期的分布. 大多数Kepler行星是所谓的超级地球和亚海王星, 少数是轨道周期很短的亚地球行星(大约是地球大小), 但没有一个接近“地球2.0”(在类太阳恒星宜居带内的地球大小行星, 如绿色框所示) (由武延庆提供)

Figure 2. Distribution of planet radii and orbital periods discovered by Kepler shows that most Kepler planets are classified as Super-Earths and Sub-Neptunes, with a few being Sub-Earth planets (approximately Earth-sized) that have very short orbital periods. However, none closely resemble “Earth 2.0” (Earth-sized planets within the habitable zone of Sun-like stars, as indicated by the green frame) (Credit: WU Yanqing)

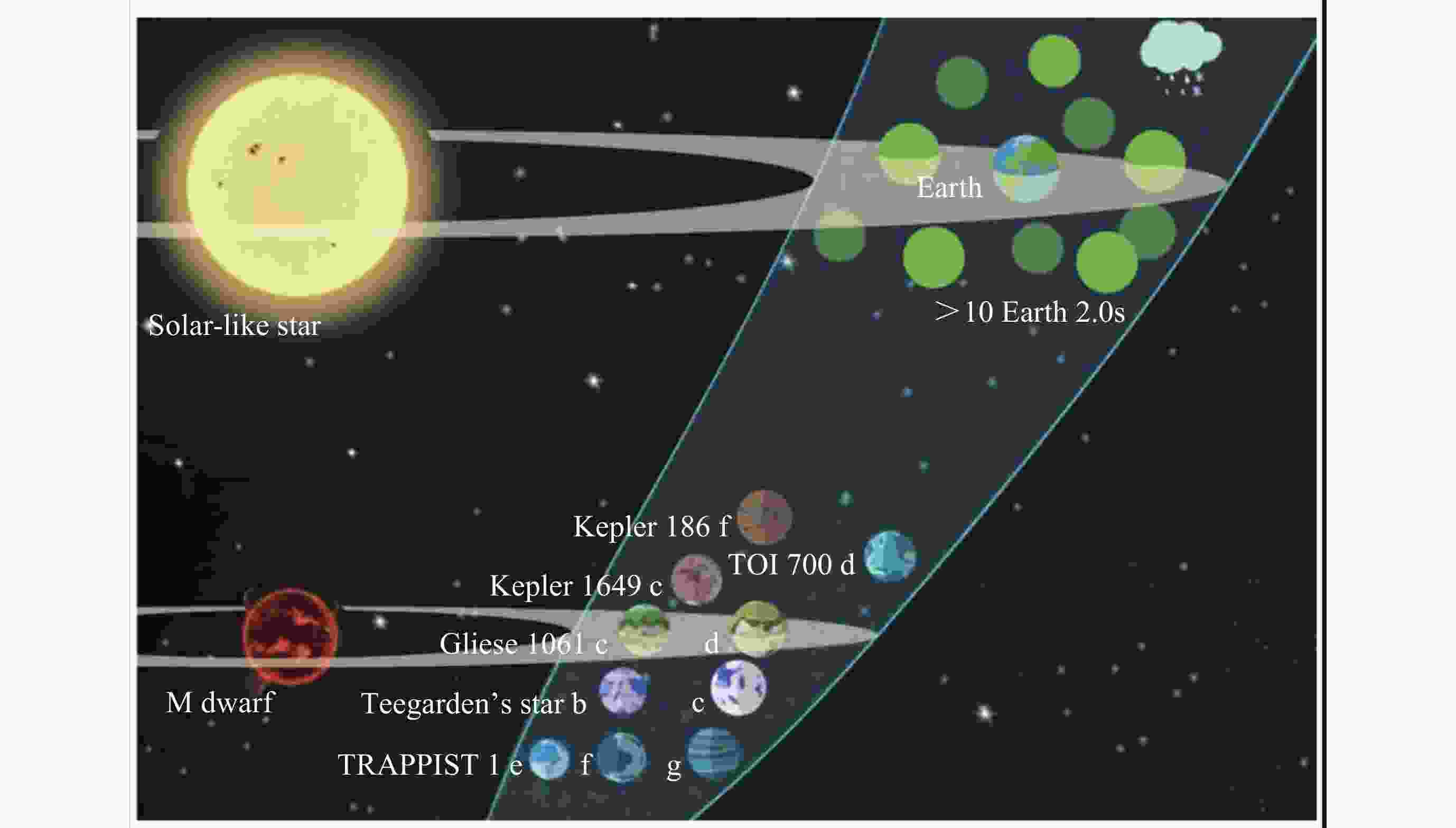

图 3 宜居带内的类地球行星. 目前探测到的处于宜居带 (蓝色阴影区域) 内的地球大小行星 (0.8 Re < Rp ≤ 1.25 Re)和未来ET预期探测到的系外地球 (地球2.0, 绿色球体). 当前所有已发现的地球大小行星都围绕M矮星运行, 这与围绕G和K型矮星的系外地球有本质不同 (由方童提供)

Figure 3. Earth-sized planets in habitable zones. Currently detected Earth-sized planets (0.8 Re < Rp ≤ 1.25 Re) within the habitable zone (the blue shaded area) and the anticipated Earth 2.0 s from ET (represented by green spheres) differ significantly in their host stars (Credit: FANG Tong)

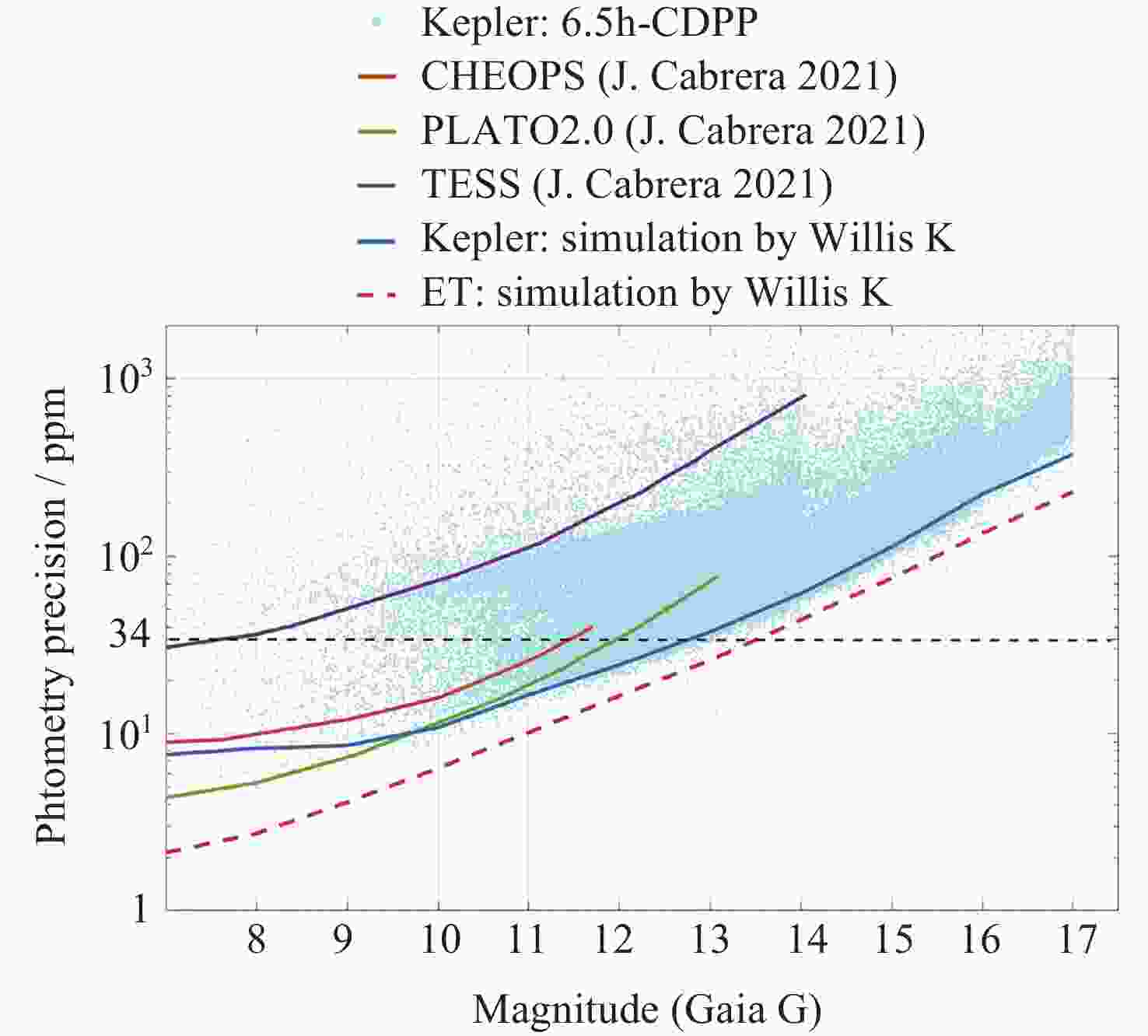

图 4 空间测光科学卫星测光精度 (不包括恒星活动产生的噪声). ET (6台望远镜叠加观测同一视场模式)与CHEOPS, PLATO, TESS和 Kepler 的测光精度比较. PLATO, CHEOPS和TESS的测光精度来自Cabrera 2021 (PLATO conference)的1 h累积结果, 将其转化成6.5 h的精度以便与Kepler和ET的6.5 h模拟结果相比较. 淡蓝点为Kepler实际恒星测光数据

Figure 4. Photometric precision of Space-based photometric space missions (excluding noise from stellar activity). ET (6 telescopes stacked observing the same field of view) compared with the photometry precision of CHEOPS, PLATO, TESS, and Kepler. The photometry precision of PLATO, CHEOPS, and TESS is derived from the 1 h cumulative results of Cabrera 2021 (PLATO conference), which we have converted to 6.5 h precision to compare with the 6.5 h simulation results of Kepler and ET. The light blue dots represent the actual stellar photometric data from Kepler

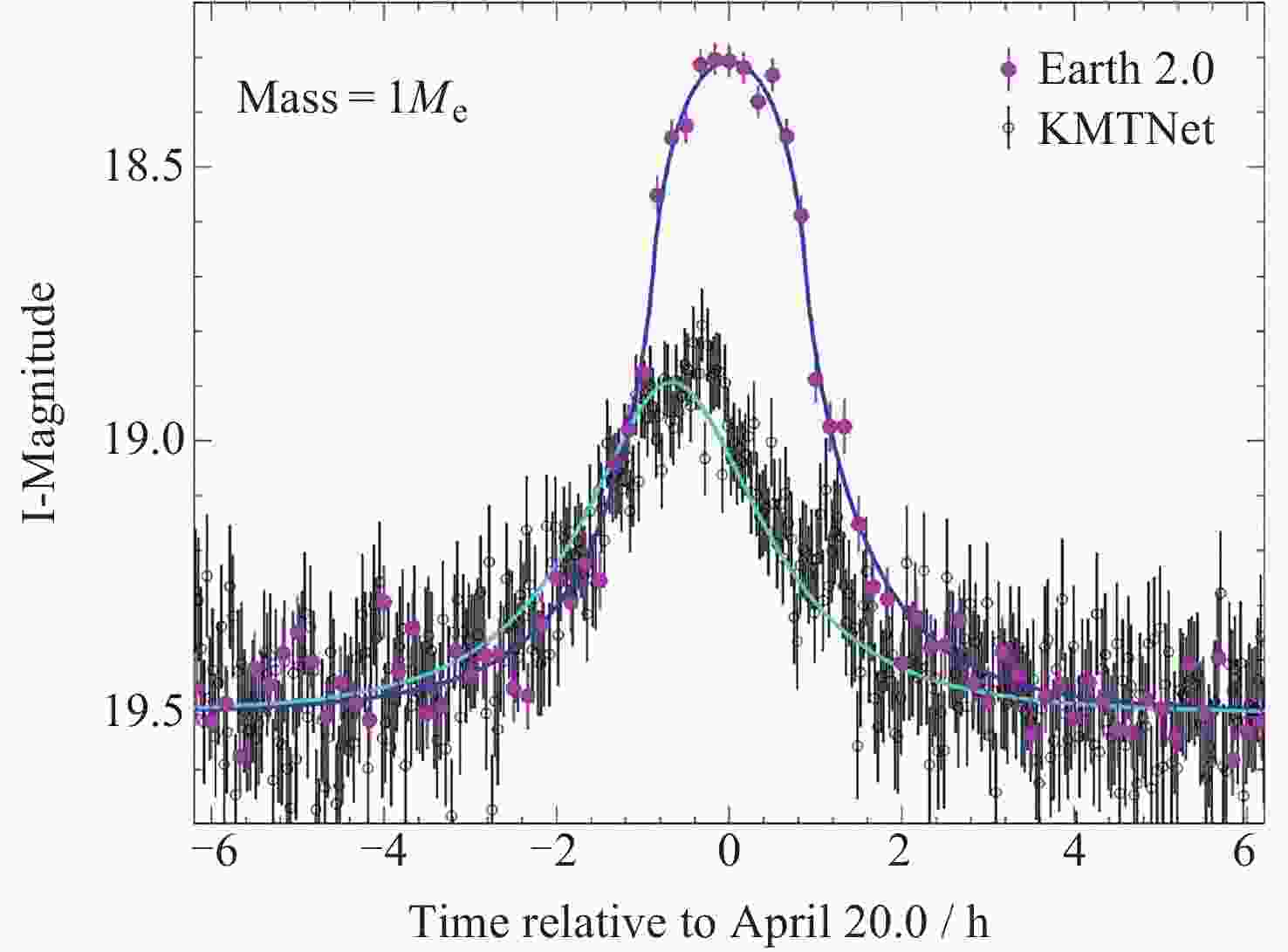

图 6 ET卫星观测的流浪地球的模拟带有高斯噪声的光度曲线(品红圆圈)和地面的KMTNet望远镜(黑色圆圈). ET数据的误差棒是使用ET的望远镜参数计算的. 连续的KMTNet数据具有1.0 min 的曝光时间和 1.0 min的读出时间

Figure 6. Simulation of the light curves for free-floating Earth-mass planet observed by the ET spacecraft, with Gaussian noise (magenta filled circles), and the ground-based KMTNet telescope (black circles). The error bars for the ET data were calculated using the telescope parameters of ET. The continuous KMTNet data have an exposure time of 1.0 minute and a readout time of 1.0 minute

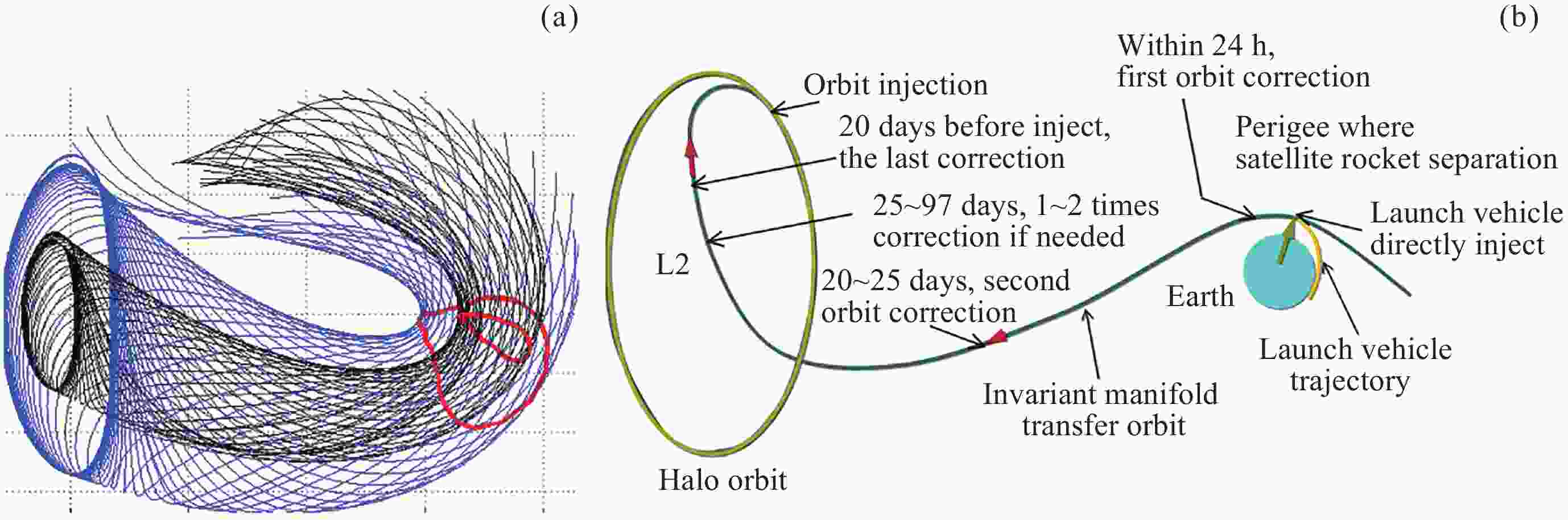

图 19 不变流形及飞行轨迹. (a)不同尺寸Halo轨道不变流形接近地球的近拱点.(b)运载直接送入不变流形轨道, 卫星自主修正入轨示例, 卫星沿不变流形转移, 中途不超过5次的轨道修正, 总转移所需时间约为117 d

Figure 19. Invariant manifolds and fiight trajectories. (a) Schematic diagram of the invariant manifold approach to Earth’s periapsis for Halo orbits of different sizes. (b) Schematic diagram of the carrier directly entering the invariant manifold orbit, with the spacecraft autonomously correcting its orbit. The spacecraft transfers along the invariant manifold, with no more than 5 orbital corrections mid-way, and the total transfer time is approximately 117 days

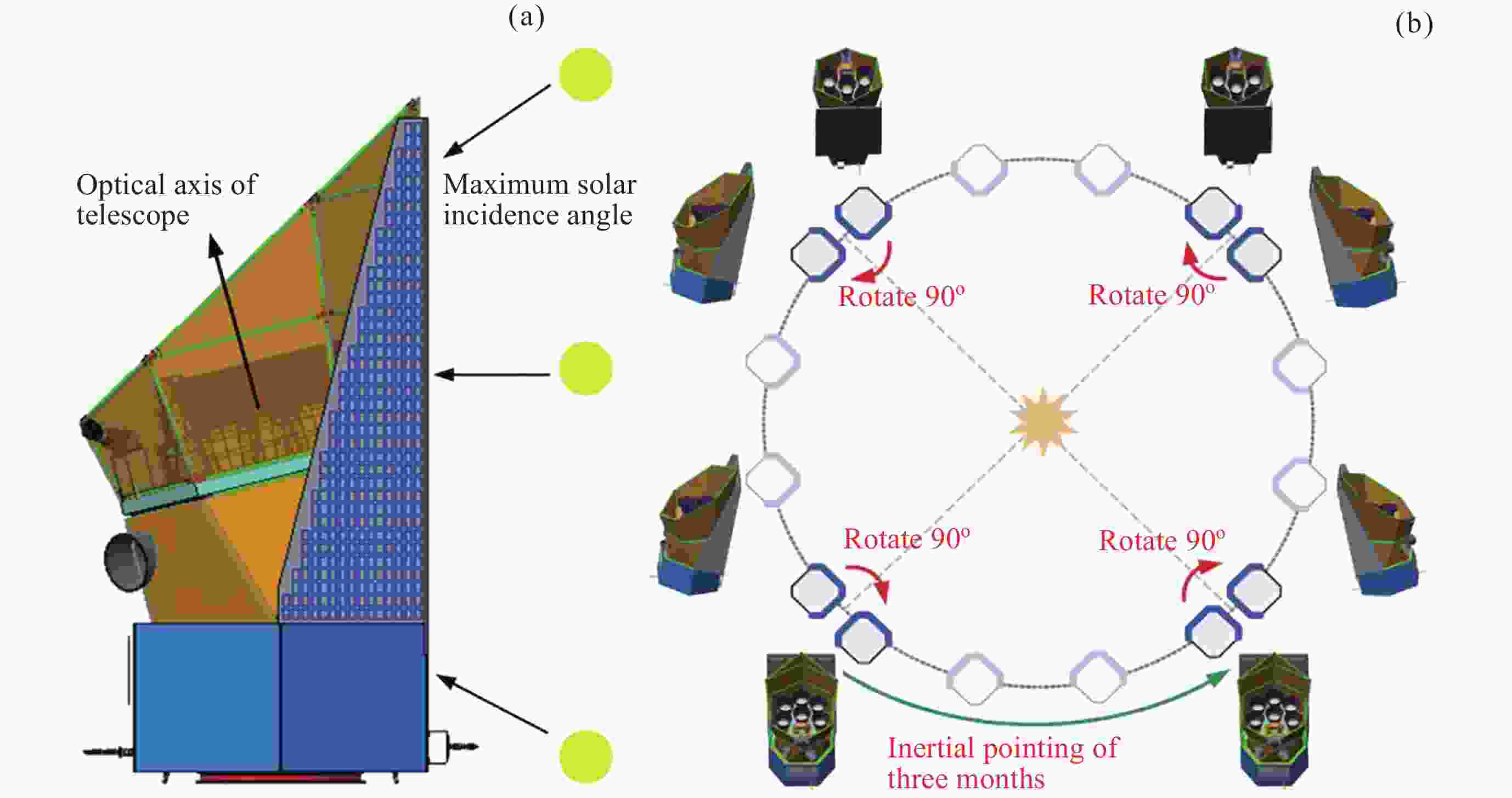

图 20 光照示意及观测策略. (a) ET卫星凌星望远镜指向开普勒天区附近时太阳入射角; (b)ET观测策略, 约每90天调整姿态, 保证能源供应

Figure 20. Solar illumination diagram and observation strategy. (a) Schematic of the solar incidence angle when the ET’s transit telescope is pointing near the Kepler field of view, (b) schematic of the ET observation strategy, with attitude adjustments approximately every 90 days to ensure energy supply

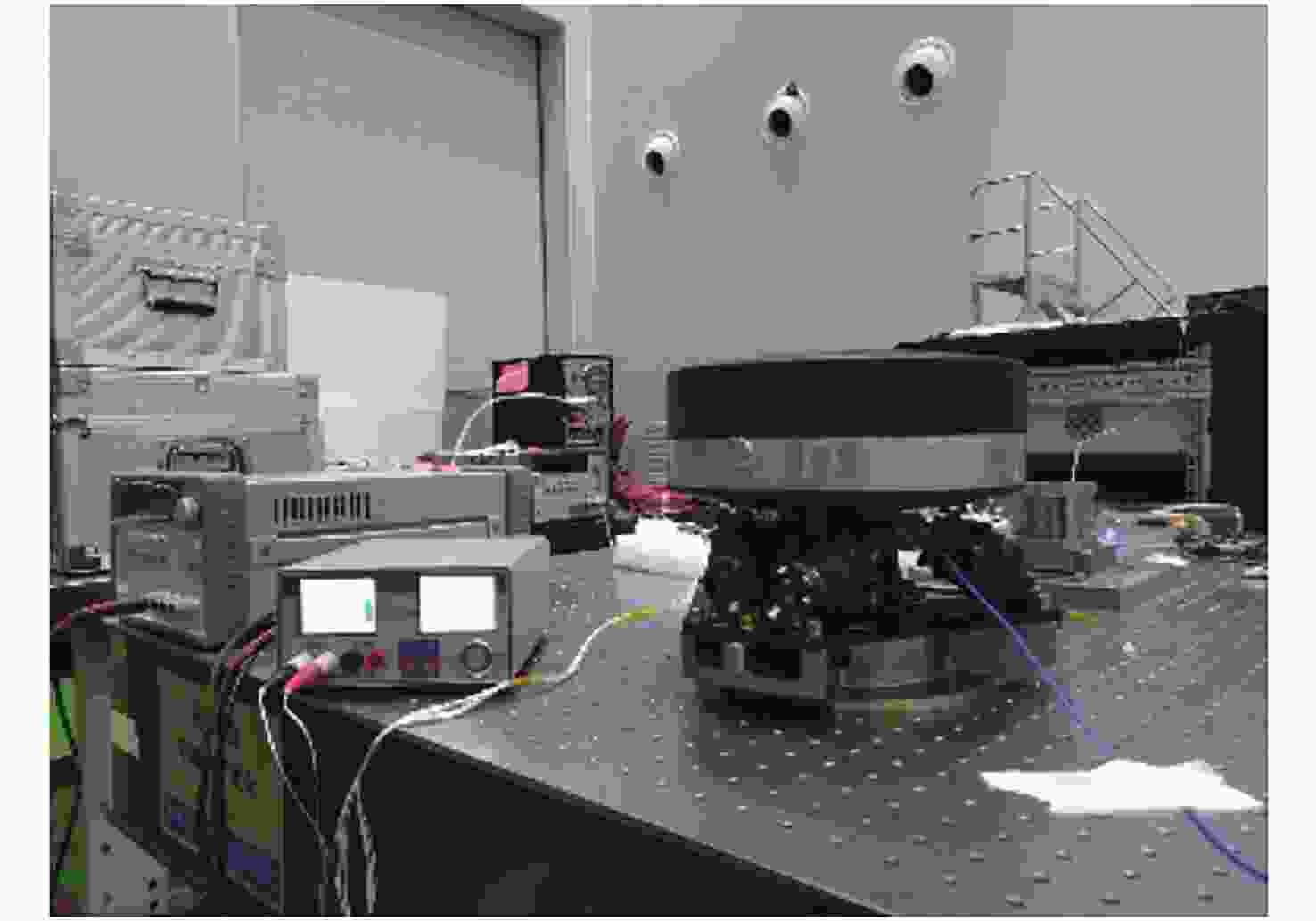

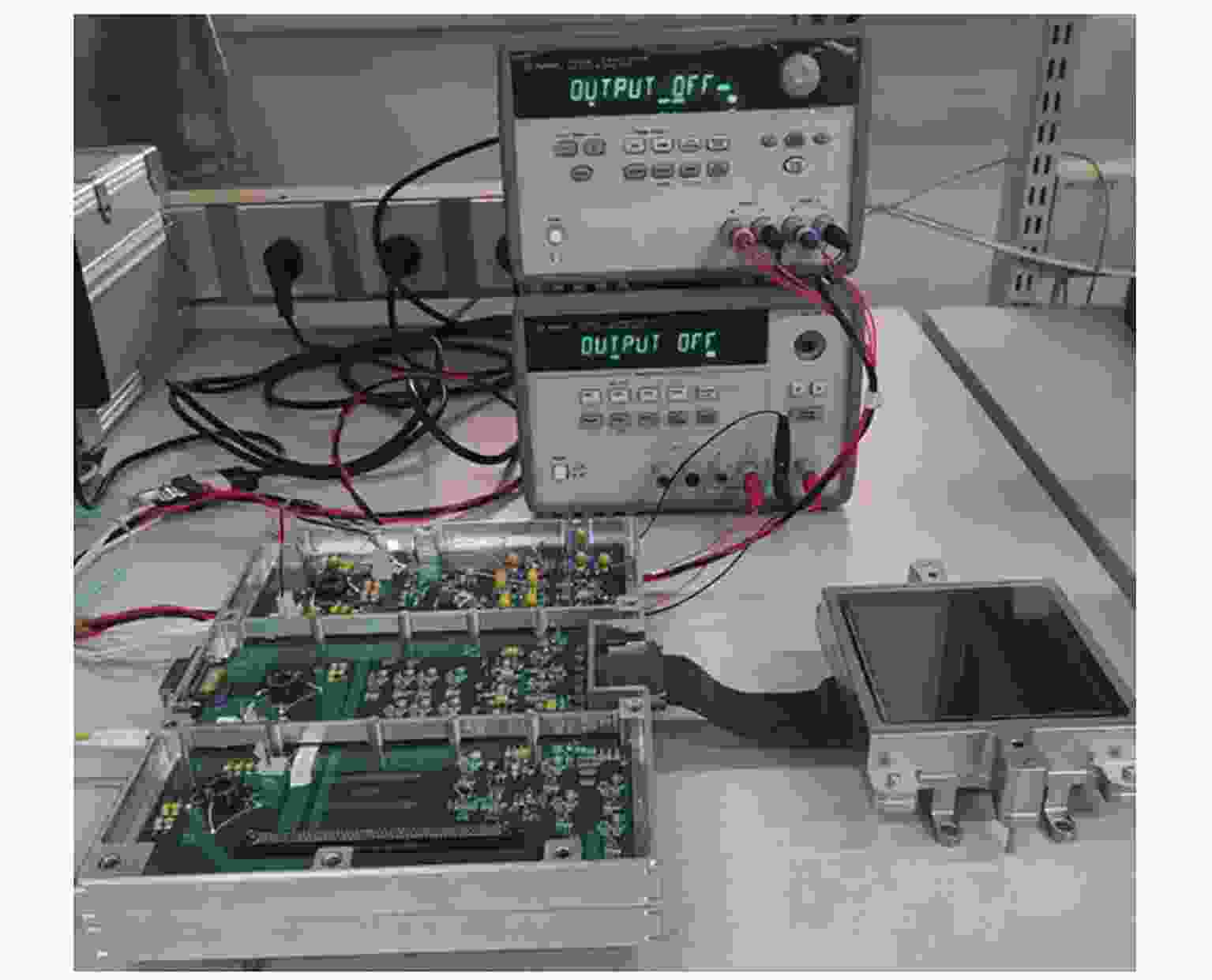

图 33 CMOS相机测试系统实物. 测试系统包括真空罐、TEC、TEC控制器、铂电阻、水冷系统、经过测试该系统可以长期工作温度稳定在小于等于–40℃±0.04℃

Figure 33. Photo of the CMOS camera testing system. The testing system includes a vacuum chamber, TEC (Thermoelectric Cooler), TEC controller, platinum resistance, water cooling system, and it has been tested that the system can work for a long time with temperature stability at less than or equal to –40℃ ± 0.04℃

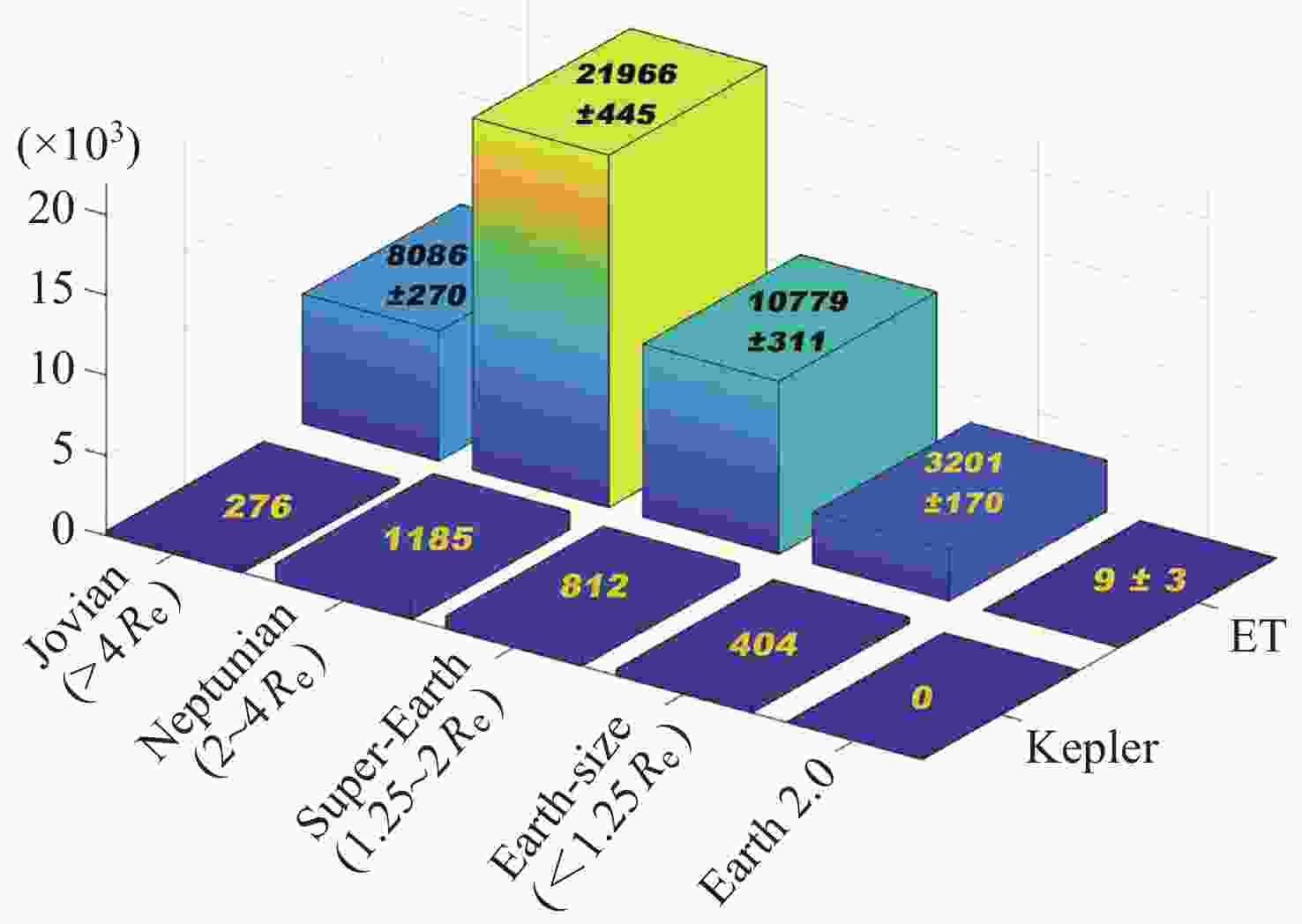

表 1 Kepler, PLATO和ET的关键性能与预期系外地球产出的比较

Table 1. Comparison of the key performance and expected Earth 2.0 yield of Kepler, PLATO, and ET

有效口径/cm 总视场

/

(平方度)测光精度

12.7等星/

6.5 h /(ppm)安静亮星数

(×103)总恒星数(×103) 预期系外地球

$ {\eta }_{\mathrm{e}}\approx $10%2年 4年 Kepler 95 105 59 2.5 175 0 0~1 PLATO 59 2000 34 5 250 0$ \text{~}\text{1} $ 2~3 ET 68 550 28 40 2000 3~4 10~20 表 2 ET有效载荷主要配置参数

Table 2. Key parameters of the ET payload

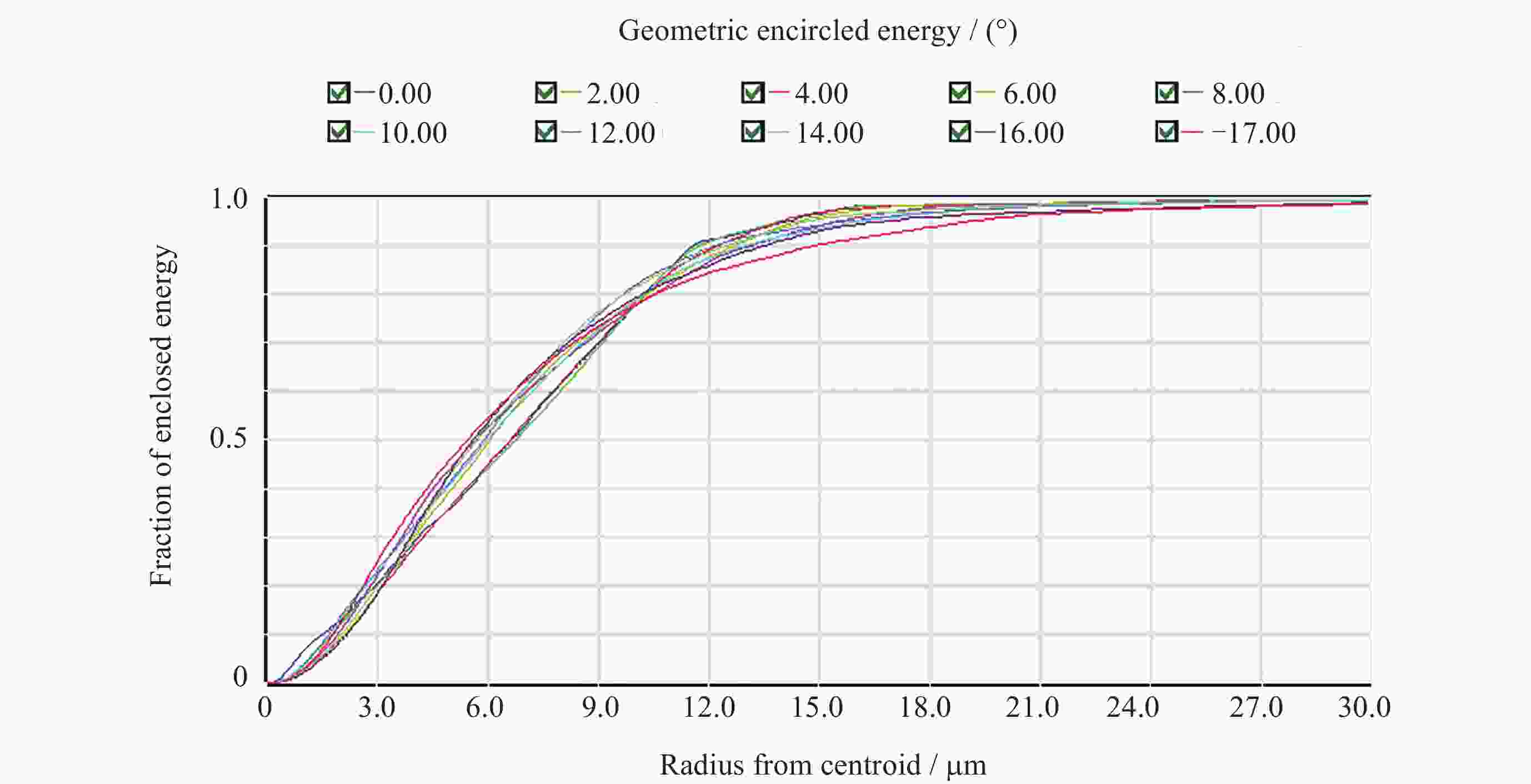

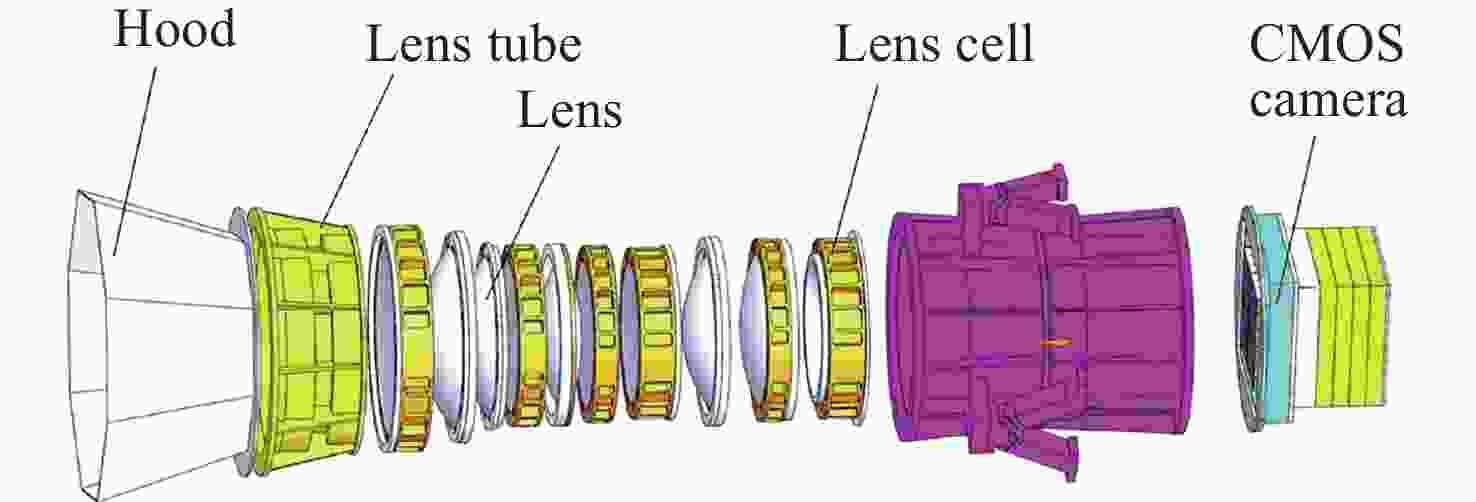

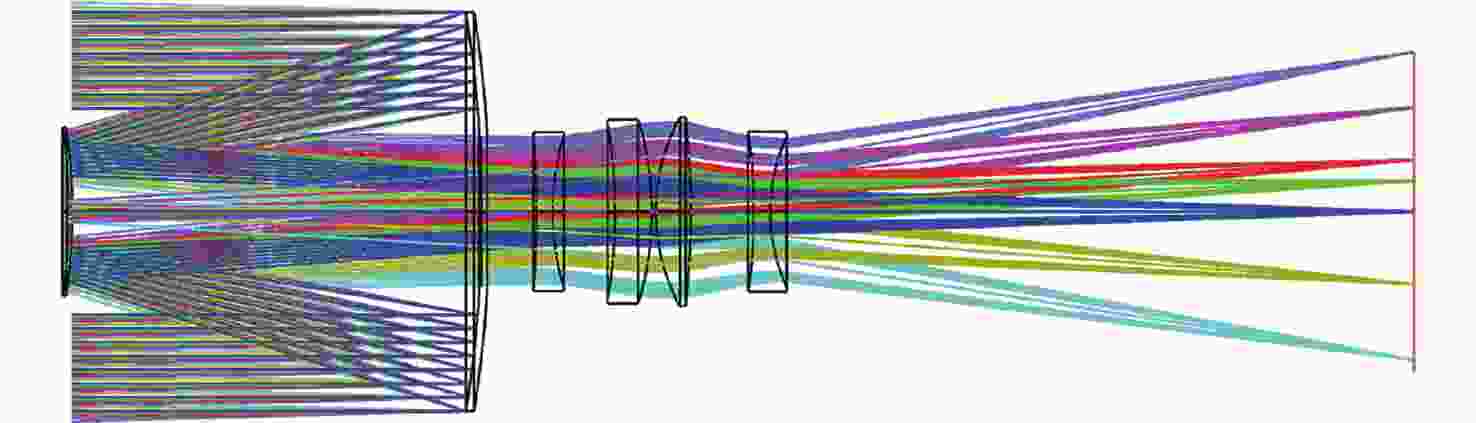

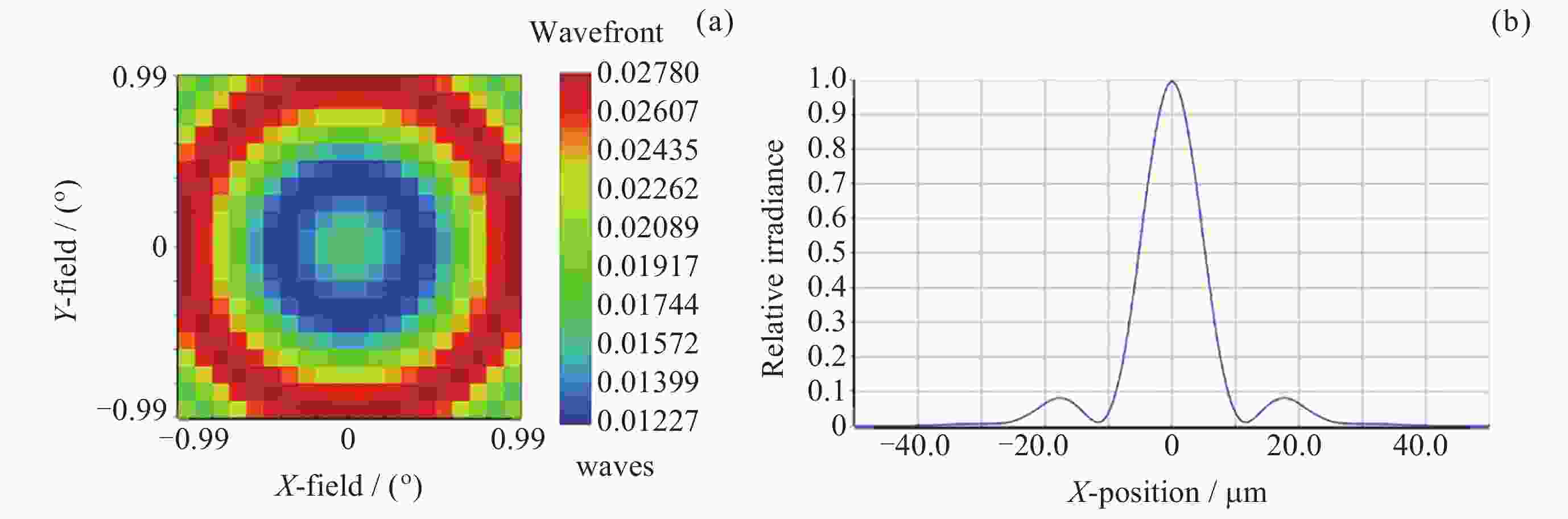

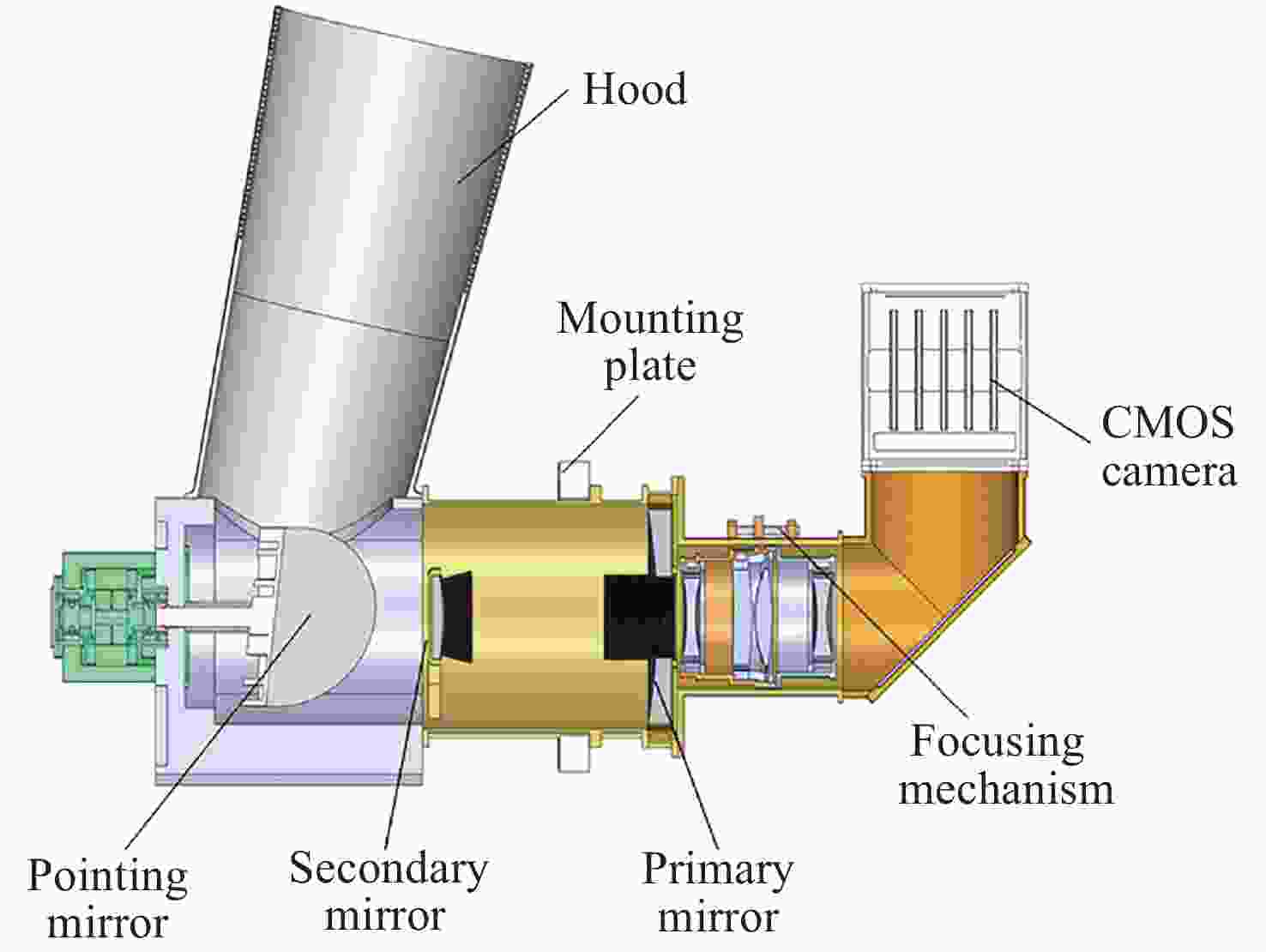

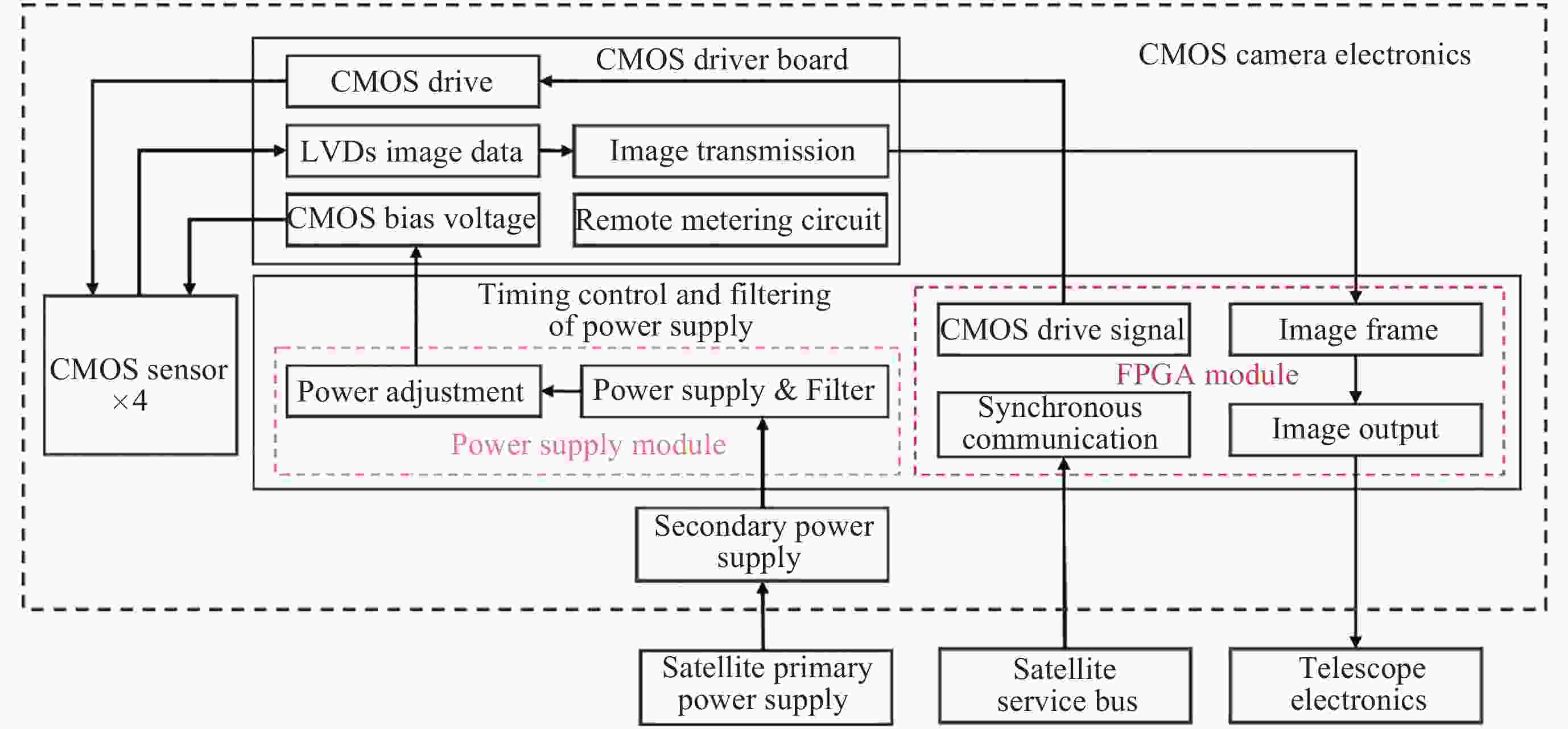

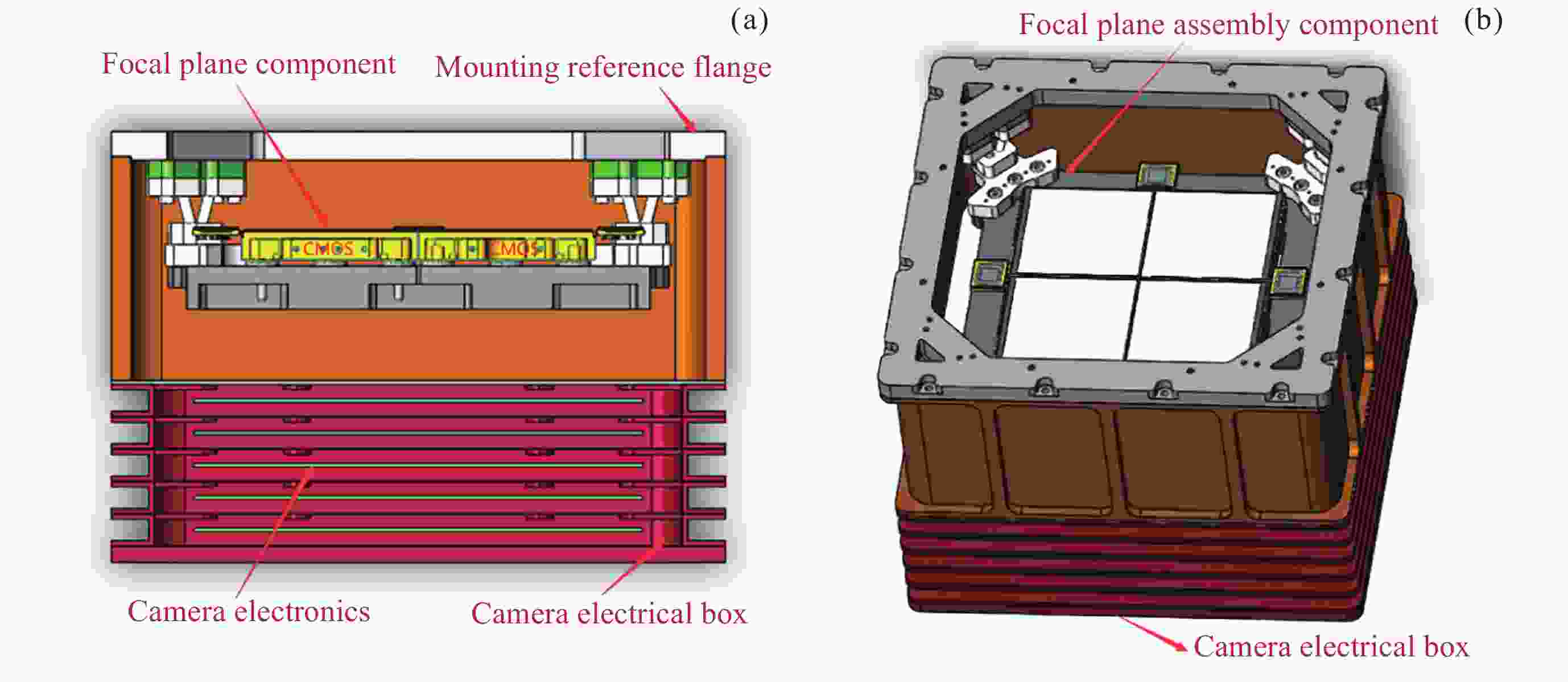

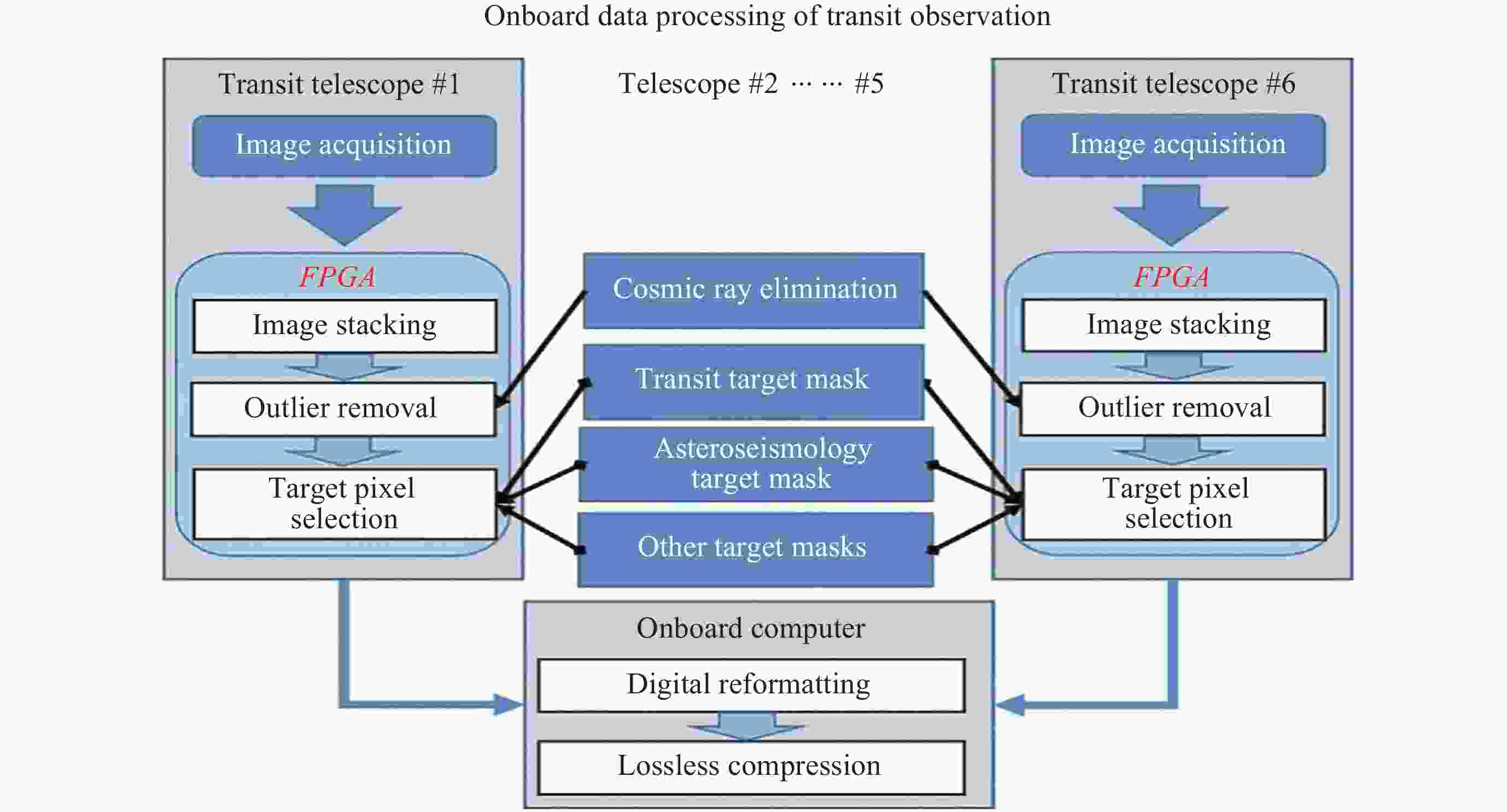

项目 凌星望远镜 微引力透镜望远镜 有效观测波段 465~940 nm 650~1000 nm 有效口径 28 cm 35 cm 像元角分辨率 4.83″ /pixel 0.4″ /pixel 有效观测视场 550平方度 4平方度 望远镜像质 EE90直径≤5 pixel FWHM≤1.0″ 望远镜温度稳定性 ≤±0.3℃ – 探测器温度稳定性 ≤±0.01℃ – 探测器暗电流 ≤0.25 e–

(s–1·pixel–1)平均≤0.10 e–

(s–1·pixel–1)探测器读出噪声 ≤7 e–/ pixel ≤8 e–/ pixel 望远镜拼接指向精度 ≤0.1° – 曝光时间 10 s 10 min 读出时间 ≤3 s 3 s 电功耗 峰值869 W, 平均764 W 重量 1240 kg 在轨存储数据量 10 Tbit 下传数据量 约730 Gbit·d–1 表 3 适用ET观测的轨道类型对比

Table 3. Comparison of orbital types suitable for ET observations

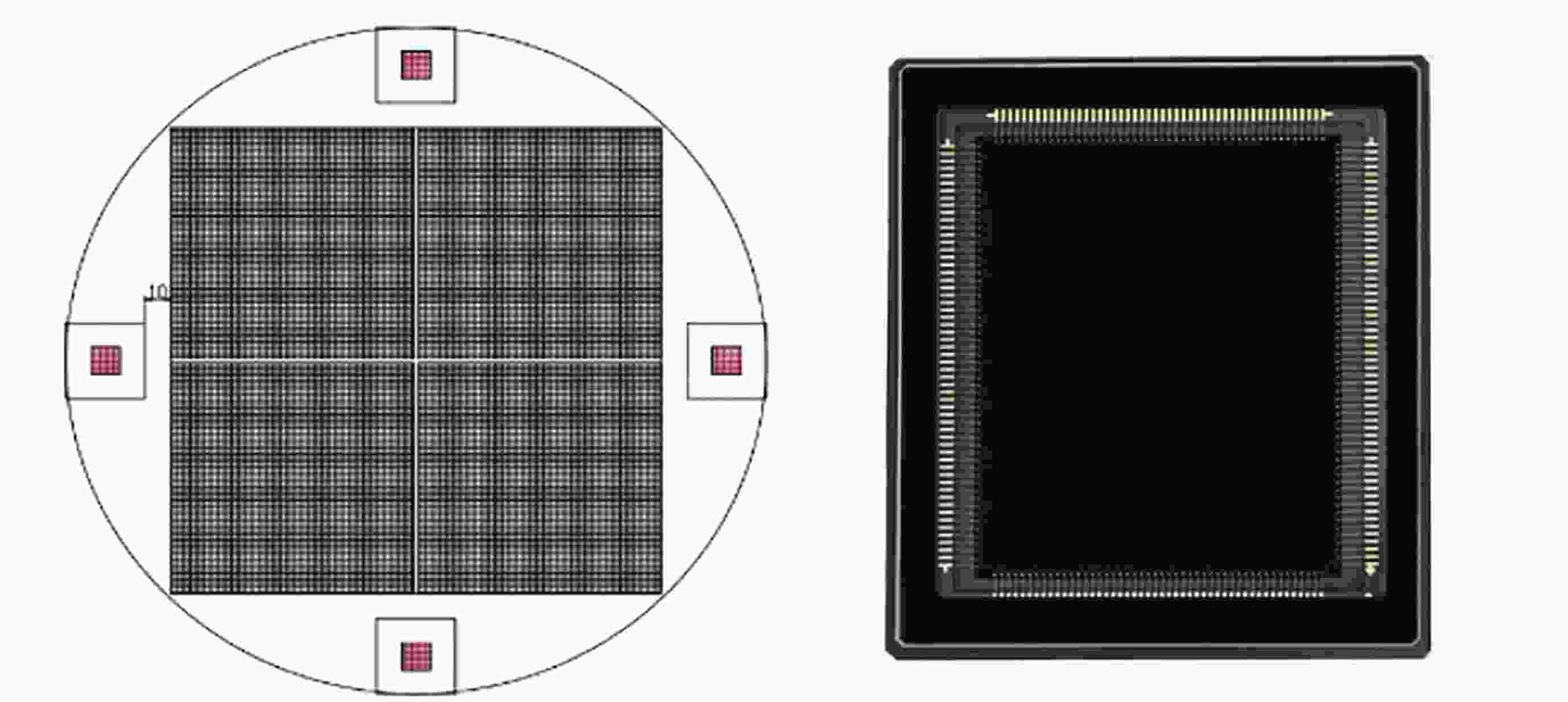

轨道类型 优点 缺点 月地共振轨道 辐射小, 日、月遮挡时间较短 轨道速度变化较大, 热流波动大 高椭圆轨道 数传速率高 穿越辐射带且热环境易受到地球影响 日心地球拖尾轨道 轨道热流稳定, 辐射低 若不轨道维持, 星地距离持续增加, 若维持燃耗较大 日地L2点的Halo轨道 热环境、辐射和光照条件较好 需要轨道维持, 但代价较小 表 4 GSENSE2020 BSI探测器特征参数

Table 4. GSENSE2020 BSI detector characteristic parameters

器件参数 参数值 感光面积 13.3 mm×13.3 mm. 每个导星视场1.62°×1.62°@凌星、8.7′×8.7′@微引力 像素尺寸 6.5 μm. 2.85″@凌星、0.26″@微引力 阵列 2048×2048 pixel 量子效率 平均70%(420~1000 nm), 峰值95%@560 nm 读出噪声 中位数1.6 e–; 3.5 e–(45 krad60Coγ辐照) 暗电流 20 e– (s–1·pixel–1) @ 25 ℃, 253 e– (s–1·pixel–1) @25 ℃(45 krad60Coγ辐照) 表 5 2通道GSENSE1081 BSI相机测试结果

Table 5. Test results for the 2-channel GSENSE1081 BSI camera

Date Gain

e–/ADUReadout Noise

e–/pixel/frameNonlinearity/(%)

10%~90% FWPTC/(%)

10%~90% FWDark current

e–/s @ –40°PRNU/(%) 1 July 1.466 4.619 0.54 0.90 0.010 0.65 4 July 1.460 4.627 0.47 1.48 0.011 0.61 5 July 1.459 4.616 0.87 2.08 0.017 0.61 6 July 1.463 4.603 0.42 1.86 0.010 0.61 7 July 1.467 4.624 0.61 1.85 0.014 0.64 8 July 1.464 4.643 0.60 1.98 0.014 0.63 -

[1] MAYOR M, QUELOZ D. A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star[J]. Nature, 1995, 378(6555): 355-359 doi: 10.1038/378355a0 [2] KASTING J F, WHITMIRE D P, REYNOLDS R T. Habitable zones around main sequence stars[J]. Icarus, 1993, 101(1): 108-128 doi: 10.1006/icar.1993.1010 [3] BORUCKI W J, KOCH D, BASRI G, et al. Kepler planet-detection mission: introduction and first results[J]. Science, 2010, 327(5968): 977-980 doi: 10.1126/science.1185402 [4] BORUCKI W J. KEPLER Mission: development and overview[J]. Reports on Progress in Physics, 2016, 79(3): 036901 doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/79/3/036901 [5] FRESSIN F, TORRES G, CHARBONNEAU D, et al. The false positive rate of Kepler and the occurrence of planets[J]. The Astrophysical Journal, 2013, 766(2): 81 doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/766/2/81 [6] HOWARD A W, MARCY G W, BRYSON S T, et al. Planet occurrence within 0.25 au of solar-type stars from Kepler[J]. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 2012, 201(2): 15 doi: 10.1088/0067-0049/201/2/15 [7] MORTON T D, BRYSON S T, COUGHLIN J L, et al. False positive probabilities for all Kepler objects of interest: 1284 newly validated planets and 428 likely false positives[J]. The Astrophysical Journal, 2016, 822(2): 86 doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/822/2/86 [8] THOMPSON S E, COUGHLIN J L, HOFFMAN K, et al. Planetary candidates observed by Kepler. VIII. A fully automated catalog with measured completeness and reliability based on data release 25[J]. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 2018, 235(2): 38 doi: 10.3847/1538-4365/aab4f9 [9] ZHANG H, GE J, DENG H P, et al. Science goals of the Earth 2.0 space mission[C]//Proceedings of SPIE 12180, Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2022: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave. Montréal: SPIE, 2022: 1218016 [10] ZHU W, PETROVICH C, WU Y Q, et al. About 30% of sun-like stars have Kepler-like planetary systems: a study of their intrinsic architecture[J]. The Astrophysical Journal, 2018, 860(2): 101 doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aac6d5 [11] GILLILAND R L, CHAPLIN W J, DUNHAM E W, et al. KEPLER mission stellar and instrument noise properties[J]. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 2011, 197 (1): 6 [12] RICKER G R, WINN J N, VANDERSPEK R, et al. Transiting exoplanet survey satellite (TESS)[C]//Proceedings of SPIE 9143, Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2014: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave. Montréal: SPIE, 2014: 914320 [13] RICKER G R, WINN J N, VANDERSPEK R, et al. Transiting exoplanet survey satellite[J]. Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems, 2015, 1(1): 014003 [14] European Space Agency. PLATO Revealing Habitable Worlds Around Solar-Like Stars[R/OL]. https://sci.esa.int/documents/33240/36096/1567260308850-PLATO_Definition_Study_Report_1_2.pdf [15] RAUER H, CATALA C, AERTS C, et al. The PLATO 2.0 mission[J]. Experimental Astronomy, 2014, 38(1/2): 249-330 [16] GE J, ZHANG H, DENG H P, et al. The ET mission to search for earth 2.0s[J]. The Innovation, 2022, 3(4): 100271 doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2022.100271 [17] GE J, ZHANG H, ZANG W C, et al. ET white paper: to find the first earth 2.0[OL]. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2206.06693, 2022 [18] GE J, ZHANG H, ZHANG Y S, et al. The Earth 2.0 space mission for detecting earth-like planets around solar type stars[C]//Proceedings of SPIE 12180, Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2022: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave. Montréal: SPIE, 2022: 13 [19] IZIDORO A, OGIHARA M, RAYMOND S N, et al. Breaking the chains: hot super-Earth systems from migration and disruption of compact resonant chains[J]. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2017, 470(2): 1750-1770 doi: 10.1093/mnras/stx1232 [20] OGIHARA M, KOKUBO E, SUZUKI T K, et al. Formation of close-in super-Earths in evolving protoplanetary disks due to disk winds[J]. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 2018, 615: A63 [21] FULTON B J, PETIGURA E A, HOWARD A W, et al. The california-Kepler survey. III. A gap in the radius distribution of small planets[J]. The Astronomical Journal, 2017, 154(3): 109 doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/aa80eb [22] OWEN J E, WU Y Q. The evaporation valley in the Kepler planets[J]. The Astrophysical Journal, 2017, 847(1): 29 doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aa890a [23] WU Y Q, LITHWICK Y. Density and eccentricity of Kepler planets[J]. The Astrophysical Journal, 2013, 772(1): 74 doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/772/1/74 [24] HSU D C, FORD E B, RAGOZZINE D, et al. Occurrence rates of planets orbiting FGK stars: combining Kepler DR25, Gaia DR2, and Bayesian inference[J]. The Astronomical Journal, 2019, 158(3): 109 doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/ab31ab [25] KUNIMOTO M, MATTHEWS J M. Searching the entirety of Kepler data. II. Occurrence rate estimates for FGK stars[J]. The Astronomical Journal, 2020, 159(6): 248 doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/ab88b0 [26] GILLON M, TRIAUD A H M J, DEMORY B O, et al. Seven temperate terrestrial planets around the nearby ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1[J]. Nature, 2017, 542(7642): 456-460 doi: 10.1038/nature21360 [27] ZECHMEISTER M, DREIZLER S, RIBAS I, et al. The CARMENES search for exoplanets around M dwarfs. Two temperate Earth-mass planet candidates around Teegarden’s Star[J]. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 2019, 627: A49 [28] DREIZLER S, JEFFERS S V, RODRÍGUEZ E, et al. RedDots: a temperate 1.5 Earth-mass planet candidate in a compact multiterrestrial planet system around GJ 1061[J]. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2020, 493(1): 536-550 doi: 10.1093/mnras/staa248 [29] VANDERBURG A, ROWDEN P, BRYSON S, et al. A habitable-zone earth-sized planet rescued from false positive status[J]. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2020, 893(1): L27 doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ab84e5 [30] GILBERT E A, BARCLAY T, SCHLIEDER J E, et al. The first habitable-zone earth-sized planet from TESS. I. Validation of the TOI-700 system[J]. The Astronomical Journal, 2020, 160(3): 116 doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/aba4b2 [31] QUINTANA E V, BARCLAY T, RAYMOND S N, et al. An earth-sized planet in the habitable zone of a cool star[J]. Science, 2014, 344(6181): 277-280 doi: 10.1126/science.1249403 [32] GUERRERO N M, SEAGER S, HUANG C X, et al. The TESS objects of interest catalog from the TESS prime mission[J]. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 2021, 254(2): 39 doi: 10.3847/1538-4365/abefe1 [33] KUNIMOTO M, DAYLAN T, GUERRERO N, et al. The TESS faint-star search: 1617 TOIs from the TESS primary mission[J]. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 2022, 259(2): 33 doi: 10.3847/1538-4365/ac5688 [34] BENZ W, BROEG C, FORTIER A, et al. The CHEOPS mission[J]. Experimental Astronomy, 2021, 51(1): 109-151 doi: 10.1007/s10686-020-09679-4 [35] FORGAN D H, HALL C, MERU F, et al. Towards a population synthesis model of self-gravitating disc fragmentation and tidal downsizing II: the effect of fragment-fragment interactions[J]. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 2018, 474(4): 5036-5048 doi: 10.1093/mnras/stx2870 [36] RASIO F A, FORD E B. Dynamical instabilities and the formation of extrasolar planetary systems[J]. Science, 1996, 274(5289): 954-956 doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.954 [37] KAIB N A, RAYMOND S N, DUNCAN M. Planetary system disruption by Galactic perturbations to wide binary stars[J]. Nature, 2013, 493(7432): 381-384 doi: 10.1038/nature11780 [38] MA S Z, MAO S D, IDA S, et al. Free-floating planets from core accretion theory: microlensing predictions[J]. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters, 2016, 461(1): L107-L111 doi: 10.1093/mnrasl/slw110 [39] BARCLAY T, QUINTANA E V, RAYMOND S N, et al. The demographics of rocky free-floating planets and their detectability by WFIRST[J]. The Astrophysical Journal, 2017, 841(2): 86 doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aa705b [40] GOULD A, JUNG Y K, HWANG K H, et al. Free-floating planets, the einstein desert, and ’oumuamua[J]. Journal of the Korean Astronomical Society, 2022, 55(5): 173-194 [41] KIM S L, LEE C U, PARK B G, et al. KMTNET: a network of 1.6 m wide-field optical telescopes installed at three southern observatories[J]. Journal of the Korean Astronomical Society, 2016, 49(1): 37-44 doi: 10.5303/JKAS.2016.49.1.37 [42] GOULD A, ZANG W C, MAO S D, et al. Masses for free-floating planets and dwarf planets[J]. Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2021, 21(6): 133 doi: 10.1088/1674-4527/21/6/133 [43] The Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA) Collaboration, The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) Collaboration. Unbound or distant planetary mass population detected by gravitational microlensing[J]. Nature, 2011, 473(7347): 349-352 doi: 10.1038/nature10092 [44] MRóZ P, UDALSKI A, SKOWRON J, et al. No large population of unbound or wide-orbit Jupiter-mass planets[J]. Nature, 2017, 548(7666): 183-186 doi: 10.1038/nature23276 -

-

葛健 男, 现为中国科学院上海天文台讲席教授, 国家创新人才, 中国科学院系外地球(ET)巡天卫星任务创始人和首席科学家. 主要研究方向为系外行星和观测宇宙学、天文技术和仪器以及人工智能在天文大数据中的应用等. E-mail:

葛健 男, 现为中国科学院上海天文台讲席教授, 国家创新人才, 中国科学院系外地球(ET)巡天卫星任务创始人和首席科学家. 主要研究方向为系外行星和观测宇宙学、天文技术和仪器以及人工智能在天文大数据中的应用等. E-mail:

下载:

下载: